How low can interest rates go?

By Gavin R. Putland

In chapter 4 of the Statement on Monetary Policy for November 2012, the RBA notes (p.43):

Rates on overnight indexed swaps (OIS) currently imply a cash rate target of 3 per cent by early 2013 and around 2.75 per cent by mid 2013...

That is, financial markets are betting on a 50bp reduction in the official interest rate, on top of the 150bp in reductions over the last 13 months. But (p.45):

Bank funding costs — relative to the cash rate — have risen by about 50 basis points over the past year, but are estimated to have been broadly unchanged since the previous Statement... The rise in bank funding costs relative to the cash rate... largely reflects the increased cost of deposits... largely in response to pressure from banks, investors and regulators globally to secure notionally more stable funding sources.

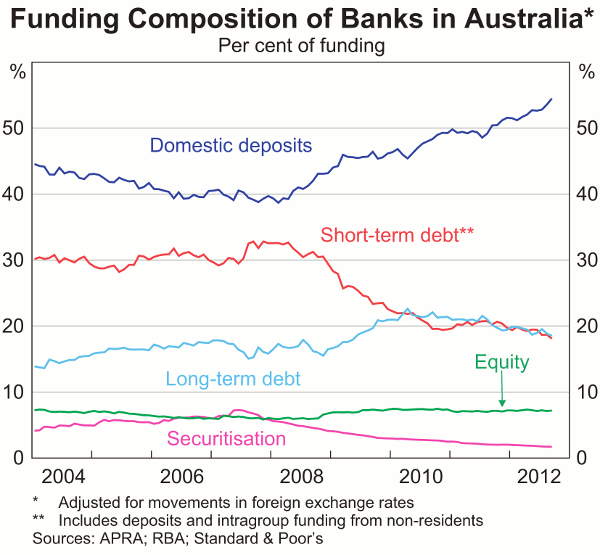

Graph 4.5 (reproduced below) shows the growth in domestic deposits as a fraction of total funding:

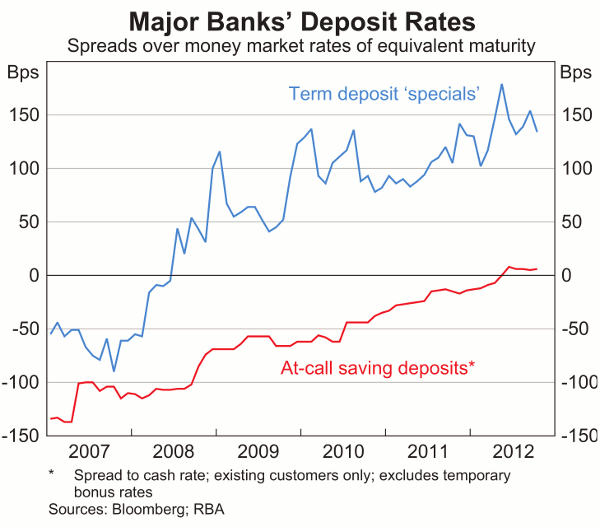

Graph 4.6 shows the generally increasing spread of term-deposit rates above money-market rates:

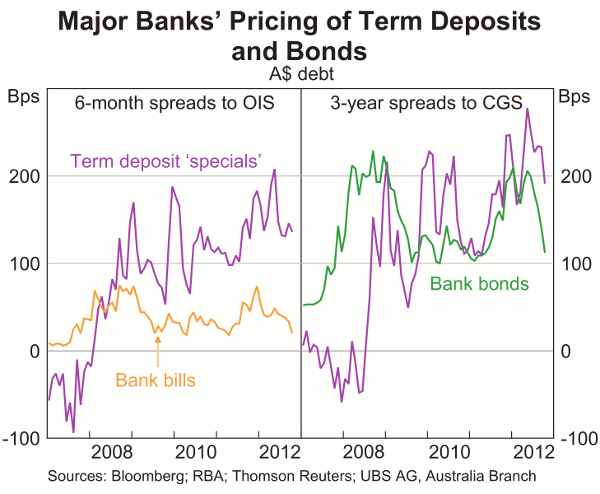

Graph 4.7 shows how term-deposit rates have exceeded those of “wholesale funding instruments”:

But term deposits are not the full story. As stated on p.44, with my emphasis:

Over the past quarter, growth in at-call deposits has been somewhat stronger than growth in term deposits reflecting the number of at-call products with yields above those on term deposit rates, particularly bonus saver accounts. In part, this reflects the inverted yield curve for maturities out to 12 months. Term deposits currently account for about half of total deposits.

The result of all these pressures, as mortgaged home owners know too well, is that cuts in the cash rate have not been fully passed on as cuts in mortgage rates.

On wholesale bank funding, the statement notes (pp.45-6):

Unlike earlier in the year, a large share of the wholesale issuance has been in offshore markets and in unsecured form... Much of this issuance has been in US dollars and for terms of 3 to 5 years.

In so far as wholesale funding is denominated in foreign currency, it is exposed to currency risk — which can be hedged, but at a price that rises with the perceived risk. A related issue is the yield of Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS), on which the RBA says this (p.43):

CGS yields remain underpinned [sic] by strong demand from international investors for AAA rated sovereign debt. The most recent data show that the share of CGS held by foreign residents was stable in the June quarter at around 77 per cent...

The high demand for AUD-denominated assets, hence the dollar itself, can no longer be explained by the terms of trade. To the extent that it is explained by the desire of foreign central banks to diversify their reserves, this too shall pass. The consequences must include cheaper (higher-yielding) CGS; and the competition from CGS must have some upward effect on bank-funding costs. A lower dollar tends to have the same effect, due to the component of foreign debt denominated in foreign currencies. These things will tend to further decouple bank-funding costs from the cash rate.

Furthermore, to the extent that the low cash rate is made possible by the disinflationary effect of the high dollar, or is an attempt to hold down the value of the dollar, any exogenous decline in the dollar is a threat to the low cash rate.

In short, it seems to me that a bet on continuing low mortgage interest rates is an increasingly dubious bet on the Australian dollar.