OECD's cure for Victoria's revenue hole

Gavin R. Putland describes the 1.42% solution.

“VICTORIA'S budget has been king-hit by a collapse in revenues of almost $1 billion...” wrote Josh Gordon in the Age today. “Just seven months ago the government predicted a $155 million surplus for the current financial year. But the updated budget figures will show predictions for stamp duty collections have been slashed by $285 million for 2012-13, with a loss of almost $1.2 billion over four years.”

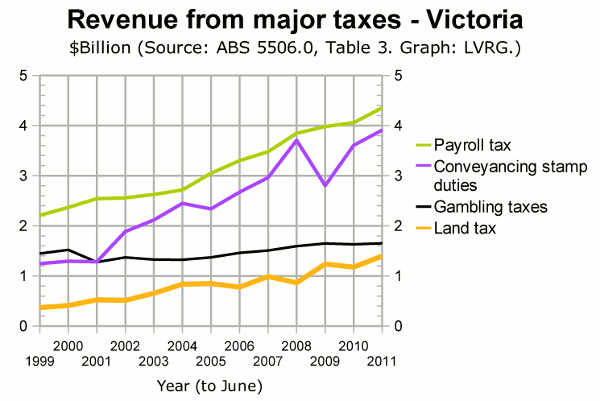

Quelle surprise! Back in May I posted this graph of tax receipts in Victoria, showing how the revenue from conveyancing stamp duty (purple) is more volatile than that from land tax (yellow).

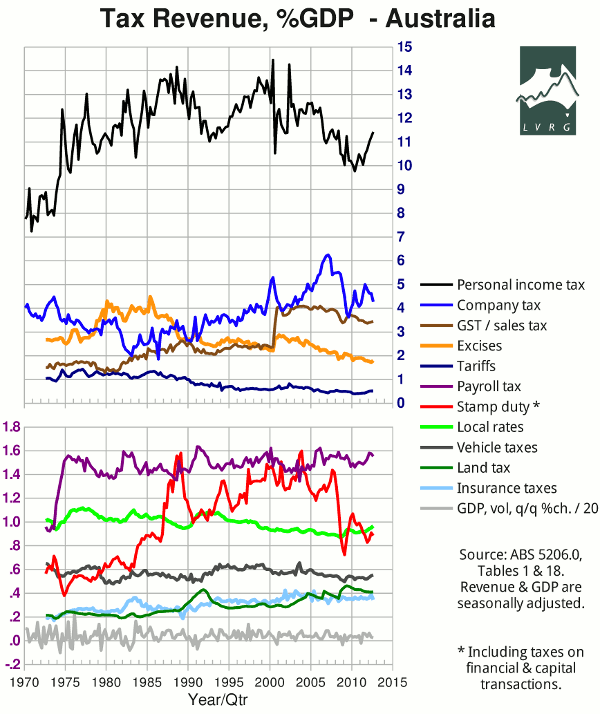

Then in September I posted a graph of nationwide tax receipts, including land tax and “taxes on financial and capital transactions” (which are mostly conveyancing stamp duty), and noted “the extreme volatility of stamp-duty revenue, on which the States foolishly rely for a large portion of their funding”. On December 5, I released an update of that graph (reproduced below), noting that “receipts from payroll tax (purple), stamp duty (red) and insurance taxes (pale blue) ticked downward”. The contrast between stamp duty and land tax (dark green) is stark.

I was reminded of that comparison by the OECD's Economic Survey of Australia for 2012, which was also released today. According to its recommendations, Australia should:

...reduce or remove conveyance duties and the progressivity of the state land tax; broaden the state land tax base by eliminating exemptions for owner-occupiers...

Quelle horreur! Cue the ritual rejections of any tax on the [genuflection] “family home”. And don't mention the fact that stamp duty itself is a great big tax on the family home, or that it taxes the value of the house (not just the land), or that it adds to the deposit gap of prospective first-time buyers, or that it gets converted into a recurrent cost by deterring home owners from moving to more convenient locations. And please don't do the sums on land tax, lest anyone think the answers are acceptable.

So let's do the sums on it. The OECD suggests that we implement a flat, broad-based land tax to replace the revenue from stamp duty and the existing progressive, selective land tax. While we're at it, we might as well replace insurance taxes, which are largely paid by property owners. To make it more interesting and more challenging, let's also replace payroll tax! (The remaining big-ticket items are gambling taxes, vehicle taxes, and fines.)

In 2010-11, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS 5506.0), Victoria received $4.354 billion in payroll tax, $1.398 billion in land tax, $3.91 billion in conveyancing stamp duty, and $1.456 billion worth of insurance taxes, making a subtotal of $11.118 billion. Suppose this revenue had been raised from a land tax using mid-2009 values (which happen to be close to the minimum values at the depth of the “GFC”). The total value of residential, commercial and rural land in Victoria at that time was $784.2 billion (ABS 5204.0 Tab.61). Then, by simple division, the required land tax rate is 1.42% per annum. That is lower than the top rate under the current progressive land tax (2.25% per annum).

What if, contrary to the second half of the OECD's recommendation, we retain the exemption for owner-occupied residential land, but impose a flat rate on the rest? The residential component of the total land value was $630.7 billion. If we assume that 2/3 of that is owner-occupied and exclude it from the total, the required rate (for the same revenue) rises to 3.06% per annum.

Instead of exempting owner-occupied residential land, we might allow the tax thereon to be deferred until the land is sold in the normal course of events, and then cap the tax bill to some fraction of the real capital gain. This deferral would meet the needs of taxpayers who are land-rich but income-poor — the ones who are invariably wheeled out for the purpose of opposing land tax outright, as if there were no other way to save them from the terrible misfortune of being asset-rich, while the asset-poor and income-poor are studiously ignored. But the deferral would cause a hiatus in revenue.

So let's start at the other end: in the long term, at what rate would a tax on real capital gains on land yield enough revenue to replace the existing payroll tax, land tax, stamp duty and insurance taxes? Let's use the revenue figures for 2010-11 (as above). The total value of residential, commercial and rural land at the end of that year (which was lower than at the beginning of the year) was $1044.1 billion. Suppose that 6% of this is sold in one year (a reasonable assumption in view of the dwelling turnover rate). And suppose that the average capital gain is 40% of the land price (at an appreciation rate of 5% per annum, that corresponds to a holding time of about 10 years, which would allow up to 10% of the stock to turn over each year, whereas we are assuming only 6%.) Then the taxable real capital gain is about $25 billion per annum, on which the required tax rate is about 45%.

Those who buy property after the introduction of the capital-gains tax could be allowed — or, in appropriate cases, required — to prepay their future capital-gains-tax liabilities in the form of an annual rate on the land value. The rate of 1.42% per annum, calculated above, would be more than enough because the affected revenue would be received earlier, not later. The “prepaid” capital-gains tax would be functionally equivalent to a land tax, and the post-paid capital-gains tax would be equivalent to deferral of the land tax.

Any of the above arrangements would capture some of the growth in land values for the State Government and therefore incentivize the Government to invest in infrastructure that enhances land values. Property owners would be better off because they would get capital gains that they would not otherwise get, due to infrastructure projects that would not otherwise proceed. Any politician who can't sell that idea should find another job.