Housing bubble exposed by ABS land values

By Gavin R. Putland

A “housing” bubble is really a land bubble. Construction costs impose upper limits on the values of buildings, but not on the value of the land under them. The land costs nothing to produce, but commands a price by reason of its scarcity and utility. And because that price tends to increase in the long term, due to increasing capacity to pay, it is vulnerable to short-term speculative bubbles during which current prices depend on belief in the greater fool.

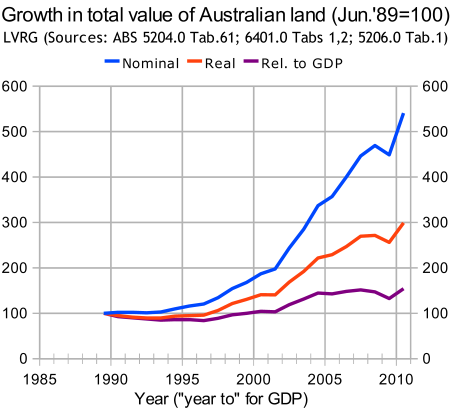

The value of land in Australia, aggregated by State/Territory and by category of use, as at June 30 each year since 1989, has been recorded by the Bureau of Statistics (ABS 5204.0, Table 61). The grand total — in raw dollars, inflation-adjusted dollars, and years' GDP, all scaled to 1989 values — is plotted in the first graph:

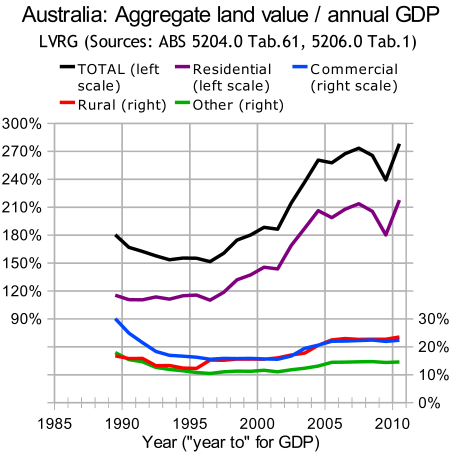

The dip is from June 2008 to June 2009. The subsequent uptick is due solely to the First Home Owners' Boost (FHOB) and its State-funded supplements, as can be seen from the second graph:

Notice that from 2005 to 2010, the fluctuations in the grand total (top, in black) are almost entirely explained by similar fluctuations in the residential aggregate (purple) while the other three categories are almost flat (although the “commercial” category should not be confused with the narrower and more volatile CBD office category).

What did the residential category have that the other categories didn't? The FHOB. How did the FHOB make residential land more valuable? In rational terms, it didn't; it merely enabled first-time buyers to borrow more.

We know from other sources that prices kept rising up to May 2010, then flatlined or slightly declined. What sustained the price rise after the withdrawal of the FHOB at the end of 2009? Nothing — except the “greater fool” theory.

Between mid 2009 and mid 2010, the total value of residential land rose from 180% of annual GDP to more than 210%. In those 12 months, where did Australia find an extra 4 months GDP to pump into land values? Nowhere. Buyers paid higher prices on a sample of sites, and that sample was deemed to be representative, notwithstanding that the buyers paid too much.

Does that mean the ABS values are wrong? No. The task of the property valuer is to measure the behaviour of the market, not to second-guess it. Discerning when the market is ripe for a “correction” is the task of economists, whose past form is not encouraging.

[Last modified Dec.4, 2010.]